The moment that the citizens of Bristol decided to give the Colston Statue some impromptu swimming lessons is the very second that British culture and history was split open, finally freed from shackles that have been built up over decades, or even centuries. A spur-of-the-moment act, it has sparked a nationwide conversation about the way we remember, and how our public spaces are used to enshrine specific historical viewpoints.

It’s something that has been long overdue. In all, only 4% of the 900 plus blue plaques that adorned walls across London acknowledge Black and Asian recipients, something that English Heritage – the body responsible – are now beginning to overhaul.

– – –

– – –

Detecting a shift in the air English Heritage curatorial director Anna Eavis confirmed that the body would be taking part in a review, rooting out historical context and providing broader viewpoints. She told the Independent: “We need to ensure that the actions and the legacies of those commemorated are told in full”.

She added: “Statues can offend but we cannot support deliberate damage to historic monuments. We believe that the best course of action is to provide as much information as possible about these monuments – their history and the context in which they were erected – and encourage debate and reflection on the sometimes painful issues they raise.”

But it’s not just about acknowledging offence and providing context – systemic erasure is also a key flaw in the way Britain deals with its heritage, a process of Whitening that pushes Black figures out of view. Nowhere is this more evident than in music, where many of our Black innovators and pioneers have been quietly forgotten, their impact and legacy under-played or dismissed.

– – –

– – –

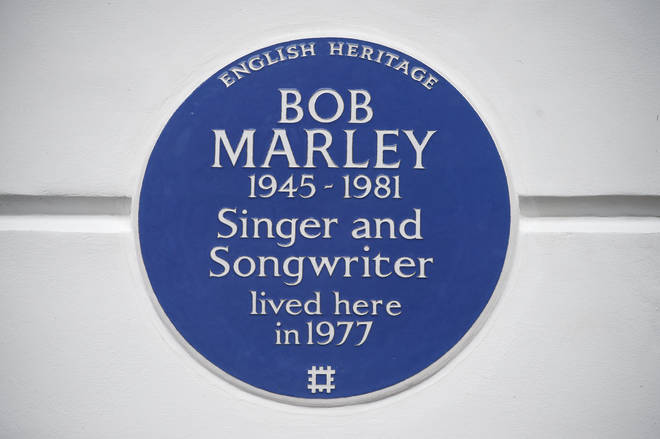

While heritage as a whole could do more to platform popular culture, its the approach to Black figures that particularly rankles. A blue plaque celebrates the life of Jimi Hendrix at his London flat – curiously, once owned by Handel in a very different era – and this was joined last year by the unveiling of a plaque in Chelsea marking the former home of Bob Marley.

It’s notable that both of these figures are marked by their proximity to whiteness – Jimi Hendrix was a rock innovator, a rare Black face in the 60s counter culture while Bob Marley’s mainstream crossover owed a huge amount to the overdubs requested by Island Records to make his reggae brew more palatable for British and American audiences.

Put simply: there’s so much more that we could do to celebrate, remember, and platform the Black voices who have pushed British music forwards.

Calypso musician Lord Kitchener became a hero to the Windrush generation, his buoyant, witty, and slyly subversive approach to immigration – ‘London Is The Place For Me’ – and his celebration of the West Indies cricket team becoming a beacon for the countless people who made the journey from the Caribbean to the UK.

He, too, undertook this journey, living in London for almost a decade and purchasing a nightclub in Manchester. He, too, deserves a plaque for his continuing cultural impact.

– – –

– – –

Fela Kuti was a child of Empire, with the Nigerian musician being sent to London in 1958 to study medicine. Quickly abandoning his stethoscope and picking up the trumpet, it was here that Fela began to fuse together jazz with the emerging sounds of highlife – spotting the soubriquet Beat (Merseybeat, Brumbeat etc) he would later coin Afrobeat, an astounding fusion of jazz improvisation, James Brown rhythms, and West African culture. In Lagos, they have a statue to Fela Kuti – in London, we don’t have anything.

Eddy Grant led Britain’s first truly successful inter-racial group The Equals to No. 1, yet he doesn’t have a plaque. Joe Strummer from The Clash – who covered The Equals’ protest song ‘Police On My Back’ – already has one.

It’s not just people – the buildings, shops, and clubs which fuel culture are also marked by this disparity. Mod hub the Flamingo has a plaque from the City of Westminster, yet the nearby Roaring 20s – a predominantly Afro-Caribbean club in the 60s – has nothing. The Wag Club in Central London has a plaque – Hackney’s Four Aces was a vital hub for East London’s Afro-Caribbean communities for decades, yet it was rewarded with demolition.

The list is endless, moving from ska pioneers to dub soundsystems, from highlife shebeens to current afrobeats innovators. London has benefited enormously from its status as an international city – on a financial level, it’s what crafted its modern identity as a financial hub, and drives its tourism industry. Culturally, though, it’s what has kept London at the forefront, a city able to communicate between different cultures, forging new styles in the process.

It’s an intricate history, one that is already being cared for by Black Cultural Archives and Black Curriculum, but it’s one that requires top-down acknowledgement from the bodies in charge of aligning our heritage. The way we remember is finally being brought into focus – it’s vital that we acknowledge and thank our Black music innovators.

– – –

– – –