Five years ago, in anticipation of a reissue of his oft-maligned ‘Pipes Of Peace’, Paul McCartney sat down for an interview with James Dean Bradfield after the Manic Street Preacher had told him of his childhood love for the record. The conversation was driven by a deeply personal, incredibly thoughtful connection to a set of songs that had been critically panned. It was obvious that here was a real student of music, interested in context, construction and intent. Bradfield is an infectious enthusiast, who pores over sleeves notes, lyric sheets and technical details.

It was back in the Eighties that he first encountered Victor Jara’s name in the lyrics of one of his favourite bands. In 2004, Bradfield told The Independent, “one of my favourite bands is The Clash and one of my least favourite albums is ‘Sandinista!’ When they became an internationalist politics band, I don’t think it worked that well.” And yet, in amongst that complicated record was ‘Washington Bullets’ and it was there the subject of ‘Even In Exile’ first registered.

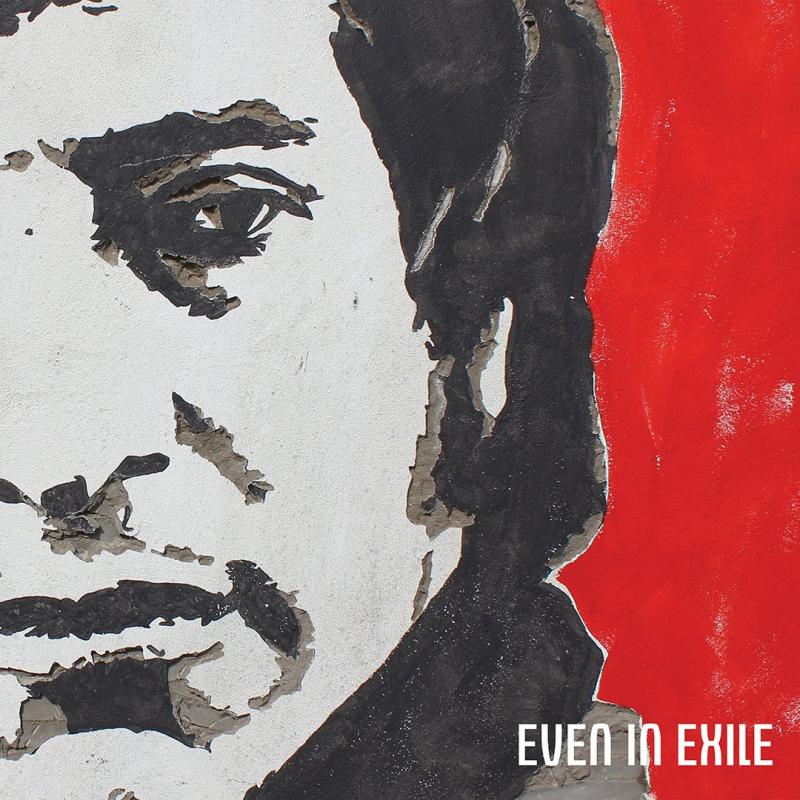

Fast forward more than thirty years and a visit to good friend, and older brother of Manics bassist and lyricist Nicky Wire, Patrick Jones prompted an entire album about the life and work of Chilean protest singer and poet Victor Jara. This project isn’t superficially affording a mention of certain names in a song, it’s inhabiting a mindset and written about a world in which slogans and shared social media posts are the closest so many get to engaging to matters of life and death.

It was a curiously prescient topic to pursue given the events of this turbulent, fractious summer that has sparked action for a number of reasons. It was forty-seven years ago when Jara was arrested after the military overthrow of Allende’s socialist Popular Unity government, having opted to return to his troubled country after touring his music so as to stand up to his enemy. Bradfield spoke to the Western Mail recently about many of us not having “that experience of standing by your beliefs and ideals when they become inconvenient towards your personal safety.” Jara’s impact was reaffirmed at the end of 2019 as his songs were once again sung during a significant protest at the Chilean government and ‘Even In Exile’ is clearly about more about values than mere biography.

The album is built around lyrics from Jones, a playwright and poet, which evolved from a writing exercise that was never intended to be published, until Bradfield took a shine to the topic and the newly-formed pieces. As he has pointed out in early promotion for the record, Jara didn’t quite fit the traditional mould for those putting words of opposition to music, highlighting his more inviting, more melodic approach. It’s a very good fit for one of the people behind ‘A Design For Life’, ‘If You Tolerate This Your Children Will Be Next’ and ’30 Year War’.

The result is a collection of absorbing, sometimes understated songs that are quite a leap from his previous solo record, 2006’s ‘The Great Western’. Textures play an important part in building the mood of each track here, as highlighted by early teaser release ‘There’ll Come A War’ with its ominous piano and shuffling, uneasy drums. It’s an exercise in not overloading a song, leaving space where he might otherwise have been tempted to apply a polish that is unnecessary.

By contrast, ‘The Boy From The Plantation’ opens like a mildly more jaunty cousin of ‘Be Natural’ from ‘This Is My Truth Tell Me Yours’, a record the Manics had been touring in full prior to the completion of this album. It also doffs its hat in the direction of The The’s ‘The Beaten Generation’, while offering up a primer on the album’s subject lyrically. It is a special song and typical of the consistent intricacy at play across the whole record.

Instrumental tracks ‘Seeking The Room With The Three Windows’ and ‘La Partida’ still possess lyrical qualities thanks to the soaring guitar of the former and the spacious ebb and flow of the latter, itself a cover of a Jara original that pitches somewhere between Calexico and Michael Price and David Arnold’s soundtrack for ‘Sherlock’. Bradfield consciously avoided trying to replicate his subject’s musical signature and had no desire to play with somebody else’s culture, instead responding to it with sounds that largely share the DNA of his main band.

Opener ‘Recuerda’ and ‘From The Hands Of Violeta’, for example, could both fit pretty seamlessly on 2018’s Manic Street Preachers album ‘Resistance Is Futile’, while ‘Without Knowing The End (Joan’s Song)’ feels like a gloriously strident tour of many of the best aspects of their deeper cuts, brooding verses giving way to a riff-driven chorus.

Hearing them in this context, it’s easy to see how Bradfield would have been drawn to Jones’ words. Having had three decades of experience in fitting the often less than concise verse of Edwards and Wire within conventional time signatures, he was well equipped to take these meditations on a life from paper to song. ‘The Last Song’ opens with the striking statement “bondaged citizens make the best revolutions” and, in reference to the brutal torture meted out to Jara prior to his death, features a chorus that also catches the ear: “They took your hands but they could not silence your tongue.”

Call it a concept album if you like, but it’s so much more than that often reductive label can indicate. These are songs about internal struggles to enact what we believe, channelling one man’s story to reflect on a world increasingly full of bluster. ‘Even In Exile’ also highlights the quite remarkable musical prowess of James Dean Bradfield who, like his one-time interviewee McCartney, has an innate capacity for compelling melodies and the skill to deliver them so beautifully. One of our greatest living guitarists has conjured up something truly special.

9/10

Words: Gareth James

– – –

– – –