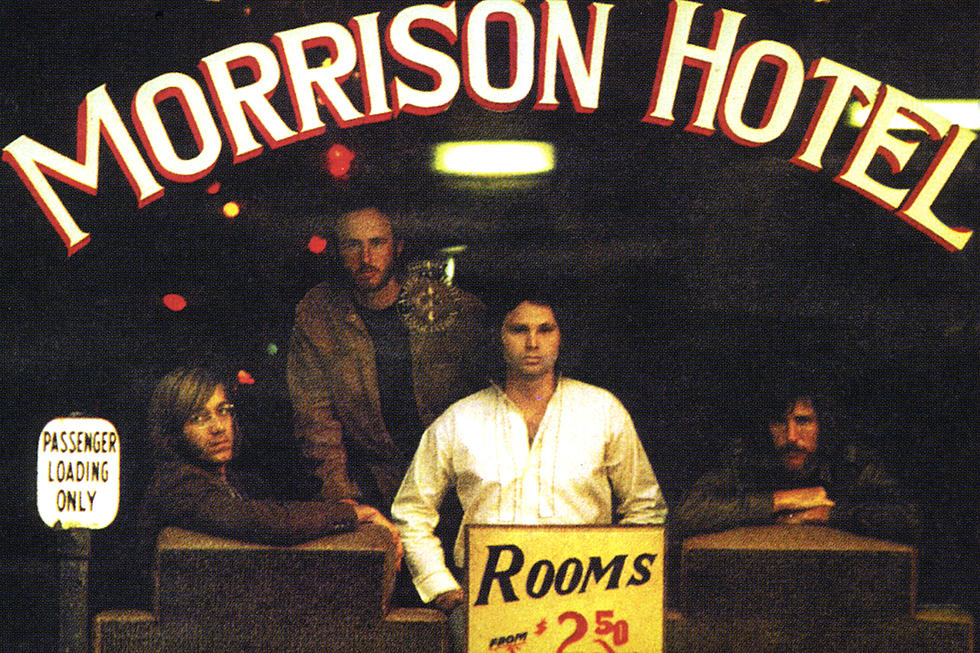

On this day 51 years ago, The Doors released ‘Morrison Hotel’, an album that stands as another piece in the puzzle that secured Jim Morrison’s place in legend as arguably the archetype of an envelope pushing rock star. Including tracks penned for his on-off girlfriend Pamela Courson like ‘The Spy’ and ‘Queen Of The Highway’, the album has become the soundtrack to the popular memory of Morrison as a tortured romantic and sex symbol.

But for some reason, history has allowed us forget that around this time in 1970, Jim Morrison was also busy setting fire to the apartment that Pamela was locked inside.

– – –

– – –

Read anything about Morrison and you’ll see him described as wild and erratic. His place in recollection of the 60s is as a beloved antagonist, rock ‘n’ roll’s Number One most wanted thanks to his numerous arrests, FBI involvement and the regular riots that The Doors concerts would incite. While his fame has endured as one of pop culture’s most rebellious icons, the corner of his legacy that deals with his violence and abuse has been erased to nothing more than another bullet point in the list of antics he got up to.

Morrison is talked about as a Jekyll and Hyde figure, with drugs and alcohol blamed for turning him into a monster. Yet time has morphed this description into something cool, using mythologised tales of his dual-souls and bad trips to blur over the stories of the underage relationships, violence towards girlfriends and fans, and even attempted murders.

If Jim Morrison was alive today, modern cancel culture would have a field day. The Blinders’ bassist Charlie articulated this perfectly, talking of his own difficulty confronting the realities of his idols; “if we knew of the abusive behaviour first then we wouldn’t perhaps give them the time that we do. We have a duty to therefore tackle our perceptions of somebody when we acquire knowledge of their behaviour but this can be very difficult to do.” This especially seems to be the case when it comes to looking back; we’re reluctant to get into a conversation about what the realities of our favourite 60s icons’ dark sides really looks like, because it simply looks a lot like abuse.

– – –

– – –

It’s such a slippery slope. When we start talking about Morrison, we have to start talking about other rock icons and their haram of baby groupies, some allegedly as young as 13. We have to start talking about Lennon’s domestic violence, Elvis Presley and Priscilla’s age gap, and the long list of other problematic details in the lives of our heroes. It’s hard to talk about one without feeling as though we’re risking an entire era of artists as the voice of cancel culture demands we wipe our Spotify library and burn our vinyl.

But we know we could never cancel the classics. Being the figureheads of an era full of events and stories that have been passed down like folklore, icons like Morrison, Bowie, and Lennon are far too engrained into culture to ever be untangled. Yet, although the argument that we should separate the art from the artist might be problematic when we talk about living performers, allowing people to escape accountability and repercussions for their actions, it may be a necessary thing for historic figures.

While their art remains relevant, the separation is necessary if only to remind us that these people existed in a very different time. It’s a fact, not an excuse, to say that the free love era of the 60s didn’t consider these things in the way we do now; assault – very sadly – was barely a word to be recognised in the lexicon. While it’s important to recognise abuse both historical and modern, resisting the insistence to judge the actions of 50 years ago by today’s standards may be the only way we can hold onto our favourite albums.

The argument of blissful ignorance feels like a necessary evil for Bowie and The Beatles. But when it comes to Jim Morrison, it feels like a different story. While other icons have become villains through a modern lens, Morrison was always an abusive figure constantly being let off because of his bad boy act.

The Doors’ drummer John Densmore has spoken a lot about Morrison’s aggression towards women, famously not visiting Morrison’s grave for three years after his death and calling him a “psychopath” who Densmore was terrified of after he walked in on Morrison holding a knife to a groupie. Even at the time, Jim Morrison was known as violent, abusive towards women, and generally destructive, but we erase these stories, along with all others against our favourite 60s icons, to keep our romanticised image of what a rock star should be in-tact.

– – –

– – –

So what do they need to be to qualify? How quickly does our image of the perfect star as wild and exciting slip into a green card for drug-fuelled chaos and violence? In an industry that’s still so male-dominated, and when men like Morrison are still largely idolised, discussing their abuses and removing the veneer of romance that surrounds them is essential for preventing their toxic behaviours creeping into 2021 under the façade of rock ‘n’ roll.

When we hold up the romanticised image of people like Morrison as perfect icons that represent what music should be, we run the risk of leaving abuse and violence as part of the parcel of stardom, like an accepted symptom of being ground-breaking.

It almost feels like we’re seeing the dangers of this play out in real time currently as more allegations come out against Marilyn Manson. In light of this, Manson’s love for The Doors and obsession with Jim Morrison (and even more violent 60s figures like Charles Manson) starts to raise an eyebrow or two. Similar to Morrison, tales of Marilyn Manson’s dark antics have always been brushed off as wild, allowed to become part of his appeal of fans – except now seeing the violent realities of this, and how the public ego-boost may have enabled his abuse, means that a lot of his behaviours start to look like red flags that were consistently ignored and shrugged off as some form of expected rock ‘n’ roll chaos.

This argument was reiterated by Devyn Crimson, a 60s inspired stylist who’s spent time with famous groupie and one of Morrison’s lovers Pamela Des Barres. “Hearing about these situations from the past can help us recognise where the line needs to be drawn and show us what can happen if we don’t,” she explained. “It would be a huge missed learning opportunity if we glossed over their problematic pasts. Plus, so many classic rock fans are very young and I think they ought to know the reality of it.”

– – –

– – –

A lot of people will read this or the numerous other pieces discussing the misdeeds of their icons, and get defensive. The Blinders’ put it perfectly; “The truth affects the way in which we interact with their art and is ultimately difficult to manage. Fans of people like Lennon, for example, do not want to have a debate about his behaviour because if they recognise it then their whole image of the man collapses.” When it comes to the level of legend that artists like Lennon and Morrison have reached in pop culture, any questioning of them feels like a personal attack against the hero of millions.

And this is exactly the problem with the romanticising musicians, past and present. All the dramatised books, podcasts and films come together to build these huge myths, forming protective bubbles around men who realistically were just great musicians. Jim Morrison was never a lizard king with two souls inside his body, Bowie wasn’t an immortal alien, one Google and the image of Elvis as the ultimate heartthrob quickly fades, and the second we realise that it becomes a lot easier to balance celebrating their legacy with recognising their wrongdoings, no longer having to tiptoe around a fragile bubble of ego-turned-myth.

And starting there would have a knock on effect, helping us stop projecting perfection onto stars so we can be less defensive when we need to criticise them as people, and handle their cases like we would any other person to help get justice for victims.

None of this is to say that you shouldn’t spend the weekend spinning ‘Morrison Hotel’. Housing some of their best tracks and some of Morrison’s greatest vocal performances, the album is a masterpiece and Jim Morrison is undoubtedly one of history’s finest performers. We can and should still celebrate that, but reckoning with the humanity of our idols and holding space to discuss their wrong-doings is essential to stop perpetuating the idea that stars are untouchable and free to do as they please.

As a poster boy for the era of rebellion, Jim Morrison will always be seen as cool but we need to untangle his violence from this perception. Knowing about his behaviour doesn’t have to stop us from saying that Morrison was ground-breaking, that his lyricism was a lesson in how to infuse rock with poetry and literary reference, and The Doors paved the way for the wave of psychedelic rock that endured into the 70s and beyond. But Jim Morrison was also an abuser who was violent and cruel to girlfriends, groupies and his peers, and this needs to be footnoted as serious and distinct from any glorified tales of his coolness.

Bursting the bubble of myth and perfection around icons, while refusing to protect abusers – past and present – is the only way to help us protect the music we love.

– – –

– – –

Words: Lucy Harbron