There’s something child-like about Donovan. Perhaps it’s his bashful laugh, his slender stature, or perhaps it’s the COVID-19 prompted elbow bump he gives us upon arrival.

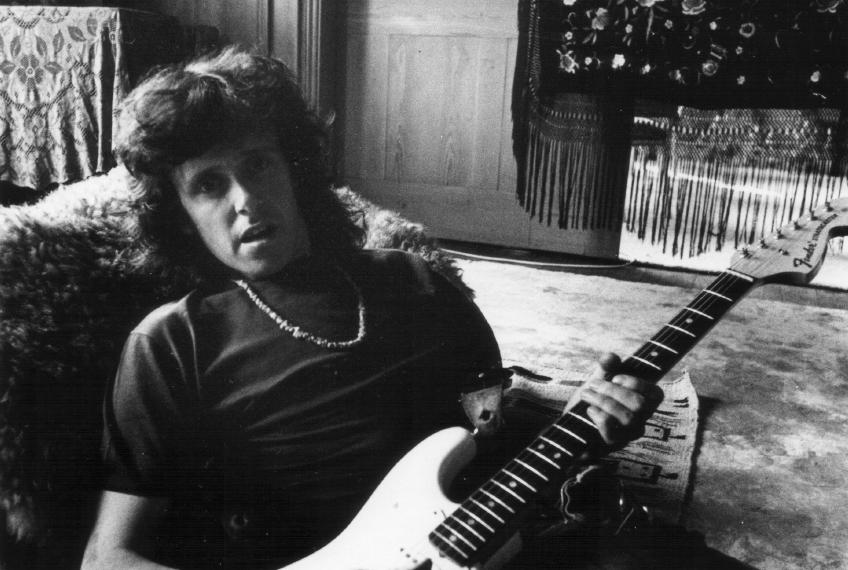

Or maybe it goes a little deeper. The Scottish born, English raised songwriter is a man of the world, someone who self-consciously inherited the troubadour mantle with Beat inspired hitch-hiking trips across the land, his acoustic guitar spread-eagled on his lap. But he’s never succumbed to cynicism – whereas many of the love generation switched off that trip for harsher chemical vibes, he held true to those principles. He’s living history, anachronistic almost – from his wardrobe to the language he uses Donovan has decided not to move on, but to remain a keen advocate for peace, love, and happiness.

“Why do I keep doing it after all these years?” he questions, his eyes scrunched up in intense focus. “It’s a mission. My father, working class read me poetry and the poetry was of noble thought but also of social change. It’s very, very deep into social change and industrial madness because that’s where the industrial revolution began here on these islands. So I was brought up around sounds of the union poetry and rebel songs from the Irish part of the family. There was always a radical element in it.”

“My dad had said to me: try to help the working man son wherever you go, because although it looks like modern times, the enslavement is in another position now and it’s called debt. And that’s what he used to say to me. That there’s a new kind of overlord and it’s called the bank.”

– – –

– – –

This year, Donovan’s path has led him to pursue green causes with a vengeance. Eco concerns have peppered his career, and the Swedish teen lightning rod Greta Thunberg has captured his imagination – new album ‘Eco-Song’ addresses this, a freshly recorded collection of songs that pepper his six decade long career. It’s a mission that returns Donovan to his roots, to the causes that have always underpinned his journey.

“Well I was absorbed in music like crazy, all kinds of music,” he says. “The fun thing like John Lennon used to say is making the music. You’re driven to do the music. It’s what you’re here to do.”

“Nobody in her generation seems to be honouring her with music. So that was the mission, right? To tip our hat to that wee lassie from Sweden, and show her our admiration and our respect.”

To Donovan, it taps into his presence within a deeper tradition of Gaelic bards, and Scots-Irish poetry. “In those days before the Industrial Revolution, there certainly was a need for to honour the four seasons,” he says. “The harvest, the gathering together, the young men and young women that would have to meet each other, the marriages, the courting, the celebration of the year… or else nobody would have ate before the factories. The whole industrial revolution after that had begun to destroy the whole system.”

“So my wife Linda told me, she said: the reason why you can do it is you are from that tradition. McCartney didn’t feel it. Lennon didn’t feel it. Dylan didn’t feel it. Morrison didn’t feel it. And so why me in 1968? I was starting to write songs calling out for all this. It’s like an operating manual for spaceship Earth.”

– – –

– – –

With manual in hand, Donovan is putting himself to work. The album is out now, and a full launch show at London’s Cadogan Hall was arranged, and subsequently postponed, with coronavirus sadly putting a halt to his forward march. Working to expand the project, he’s helping to construct a stage show – “a play, a musical… it’s one for the bucket list!” – which he had hoped to bring to his birth city of Glasgow for the UN Climate Change summit later this year.

“There four elements that have actually created this problem, this disaster, this industrial revolution that began and has now become a monster that doesn’t seem to be able to be tamed,” he says, pausing for emphasis.

“Education, the minister of education. What’s his opinion? Where is he? Who is he? The church, the church who really should be handling the situation to the corporations who only are interested in specialisation. Meaning: let’s get the best students to make the best new invention so we can make the best new product to beat arrivals. The corperations, the education, and the church, and the government. There’s four elements here and they’re all gathering. Isn’t it strange? I’m a Glasgow boy and they’re all going to gather in the largest numbers possible at the end of this year. I can’t work out this timing.”

The world works in mysterious ways, we point out. Has he always felt this urge to spread the message, Clash asks? Right from the start of his career, Donovan has handed out these missive in song form, gig to gig, show to show. “The job that I took on in the early mission was that out of invading popular culture with Bohemian ideas,” he points out. “I realised that to actually blend the pop sensibility with meaningful lyrics, they’d want to know about my favourite colour. By the way, it’s purple.”

“My favourite meal at the time was with double eggs, chips, and beans ‘cause Gypsy Dave (his famed counter-cultural compatriot) and I had just come off the road. We were hitch-hiking, so double eggs, chips, and beans was like a feast when you had no money. If we could buy a meal at a truck stop, it was always double eggs, chips, and beans. But then when we arrived in the West End in Tin Pan Alley I was then discovered in a club, signed to publishing, and round the corner was a little Greek restaurant. We’d go into the Greek restaurant and what was there? Scampi, chips, and mushrooms! Now this was definitely an upgrade, but when we had a wee bit of money, the order was simple. Double scampi, chips and mushrooms.”

– – –

– – –

Try as he might, Donovan can’t steer away from the 60s for long. A friend of the Beatles, he hero-worshipped Dylan, and found success on both sides of the Atlantic and beyond – indeed, his late summer evening feel often makes for a more refreshing listen than most of his more rebellious peers.

He’s easy to pigeonhole, perhaps, but difficult to shake off. Listening to his lengthy, probing, answers, the outwardly meandering paths his mind takes give way to a certain kind of logic. These bulbous, flowery sentences grow through outcrops in his mind, but they always flower into something remarkable. In fact, it’s probably contagious.

“A lot of people in their ‘60s tried to go back to nature, but while you were fixing this bit, another bit was being destroyed,” he shrugs.

There’s that decade again. The love generation quickly dissipated into cynicism and self-regard, Clash points out – its legacy doesn’t have the tangibility that many of its architects sought.

“The ‘60s were a question, not an answer,” he responds, like a kindly teacher. “They said in the 70s to my generation: it failed. Peace and love failed. It didn’t work. You didn’t change anything. I said, no – because it wasn’t an answer that was we were looking for. It was a question. Why is the most advanced species on the planet bent on a suicidal admission to destroy the very planet that they’re living on? Does anybody have the answer?”

Amid the anxiety and confusion of 2020, Donovan’s devout embodiment of bohemian innocence seems wildly out of step but wonderfully refreshing.

“We can’t all be feeling the same thing,” he says at one point in our conversation. “And there’s gotta be hope… because hope springs eternal.”

– – –

– – –

‘Eco-Song’ is out now. Find Donovan online HERE.

Join us on the ad-free creative social network Vero, as we get under the skin of global cultural happenings. Follow Clash Magazine as we skip merrily between clubs, concerts, interviews and photo shoots. Get backstage sneak peeks, exclusive content and access to Clash Live events and a true view into our world as the fun and games unfold.